The way we are changing is changing. The predominant approach to change has been to mandate it. An elite, at the top of the organisation, perceive a need for change and direct others to implement it. They will anticipate some resistance and have some strategies ready to overcome it. Often this change will involve some type of restructuring.

There is mounting evidence that this type of change doesn’t work very well and may actually deplete rather than add value. For some organisations, the frequency of this type of change results in a series of self-inflicted, debilitating injuries.

A recent Bain & Company study of 57 major reorganizations found that fewer than one third produced any meaningful improvement in performance. Some actually destroyed value.

Mandated change, bold strokes and long marches

Twenty years ago, in her book The Challenge of Organizational Change, Rosabeth Moss Kanter and her co-authors identified two types of change, bold strokes and long marches. Bold strokes are big strategic moves, such as buying another company, generating a large capital investment, or developing a new product. Bold strokes are usually mandated by the actions of “one or a few people”.

Long marches are more operational initiatives such as merging departments, transforming quality or customer relationships. According to Rosabeth Moss Kanter, “they require the support of many people and cannot be mandated in practice”

Of course we will continue to need a degree of mandated change, and other stakeholders such as government will mandate external change. We just need to hope that the skill and ability to design and manage change will improve.

Too frequent use of restructuring will come to be seen as the corporate equivalent of the old medical practice of blood-letting and a sure symptom of dysfunction.

According to Rosabeth Moss Kanter, long march change will have more dependable long term results and is more likely to change culture and habits. She then elaborates on the enduring foundation of sustainable organisational change – decision making.

Every large and complex organisation has many thousands of people who have each day the opportunity, or are literally required, to take action on something. We think of these as “choice points.” For an organisation to succeed in any long-run sense, these millions of choices must be more or less appropriate and constructive day in and day out. But this is an immensely difficult problem, because it requires the ultimate in decentralisation – literally to the individual level – along with centralisation in the sense that those individual choices must be coordinated and coherent.[1]

This same theme is echoed two decades later by Marcia Blenko in the Harvard Business Review:

In reality, a company’s structure results in better performance only if it improves the organisation’s ability to make and execute decisions better and faster than its competitors.[2]

Her she is elaborating on the centrality of decision effectiveness in sustaining effective change.

The engagement connection

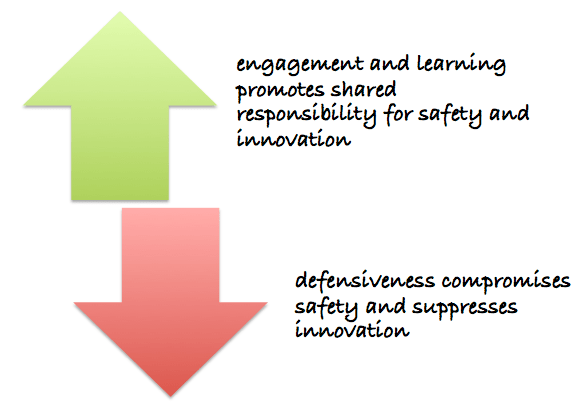

Marcia Blenko’s establishes a link between decision effectiveness and employee engagement. Rosabeth Moss Kanter emphasised the importance of “choice points” throughout the organisation. And while the focus is on big business, even small businesses manifest thousands of choice points if we consider all employees and stakeholders.

Embedding a stakeholder ethos (including employee engagement) throughout the organisation will build resilience and adaptive capacity. Over time, it is more likely that those highly engaged staff will be making decisions and choices aligned with the best interests of the company. And over time there will be less need for mandated change.

[1] Rosabeth Moss Kanter, Barry Stein and Tod Jick. The Challenge of Organizational Change: How Companies Experience It and Leaders Guide It. New York: Free Press, 1992, page 492, 495

[2] The Decision-Driven Organisation, by Marcia Blenko, Michael Mankins and Paul Rogers In Harvard Business Review June 2010, page 57