Last week the NASA astronaut Ron Garan, and the great Muhammad Yunus addressed the Global Social Business Summit. They conveyed a similar message, but from totally different perspectives. Ron Garan is one of those elite who have seen the planet from the outside, and as with several of his peers, the experience had a transformational impact. They see things from a new perspective – the “orbital perspective”. Svetlana Savitskaya, the first woman to walk in space expressed it this way:

When in orbit, one thinks of the whole of the earth rather than one’s country, as one’s home.

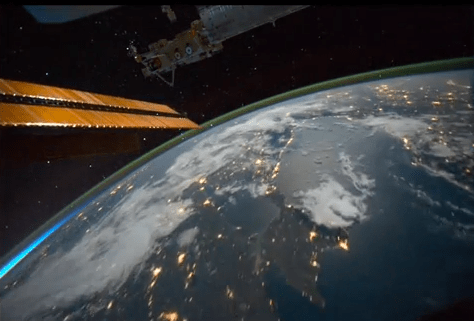

At the conclusion of his talk, Ron Garan presented a spectacular video of the return to earth of his spacecraft, Soyez TMA-21 in September this year. Here is a short segment from YouTube. (The music is Peter Gabriel’s Down to Earth).

Soyez TMA-21 re-entry

Muhummad Yunus connected back to Ron’s talk beautifully stating how it is an “unfortunate thing that we can’t keep this home as a home for a happy family”. He then spoke about the worm’s eye perspective. When he returned to Bangladesh from study in the United States, his country was experiencing warfare and famine. He found his economic theories hollow and impotent in the face of human tragedy. When he went to the neighbouring village he learned about life from the ground level – the worm’s eye view. Here he is explaining the concept.

The bigger you grow – the more distant you get away from the ground level.

Muhammad Yunus’s strength is his ability to operate from both perspectives.

Following Ron Garan’s space experiences he has dedicated his efforts to improving life back here on earth. He is a member of Engineers Without Borders, the founder of both the Manna Energy Foundation and Fragile Oasis.

Although Ron Garan adopted the posture of a student before the master (Muhammad Yunus), both men epitomise the quality of leadership required for our “fragile oasis”.

The higher ambition leader

On reading Harvard Business Review’s September 2011 article, The Higher Ambition Leader, I am struck with the parallels to the concepts championed by Muhammad Yunus and Ron Garan. The article extols the leadership by CEOs of companies such as Standard Chartered, an international bank. The bank’s vision is to be “the world’s best international bank” by “combining global reach with deep local knowledge to become the ‘right partner’ for its customers”.

The article is centred on studies of three companies whose CEOs manifest higher ambition:

to create long-term economic value, generate wider benefits for society, and build robust social capital within their organizations all at once.

These lofty ideals are achieved through creating powerful strategic visions, world class levels of engagement and a constant leadership focus on achieving the strategy.

The link to engagement

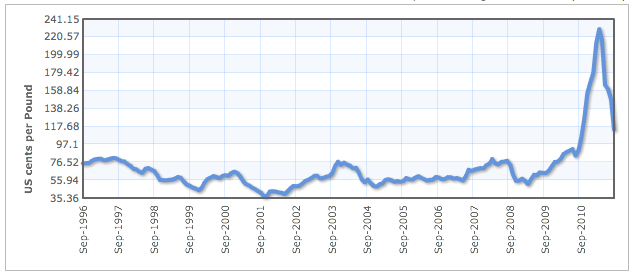

The examples of Ron Garan and Muhammad Yunus, alongside the three companies featured in the HBR article illustrate the importance of engagement. Campbell Soup’s CEO “relentlessly drove progress on two measures: total shareholder returns and the level of employee engagement”. Employee engagement levels at Campbell Soup exceeded Gallup’s benchmark of 10:1 for world-class engagement. By 2010 the company achieved “a ratio of 17 engaged employees for every actively disengaged one”. Is it a coincidence that, for the six years up to 2010 Campbell Soup achieved a cumulative total shareholder return of 64% (S&P packaged food index return is 38% and the S&P 500 return is 13%)? I don’t think so.

The leadership described here is becoming the default standard of leadership. We need leaders with both the worm’s eye view and the orbital perspective – those who can focus on the needs of their communities and companies, while also committing to sustaining our fragile oasis and its communities.