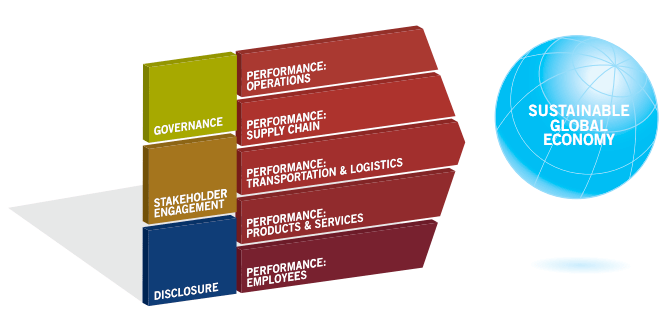

To map stakeholders, AccountAbility’s approach is to rank each stakeholder with a number of factors. This approach provides some scaffolding to enable a more objective assessment. Here is a summary of these factors from an earlier version of AccountAbility’s AA1000SES.

- Responsibility – the organisation has, or in the future may have, legal, financial and operational responsibilities in the form of regulations, …etc.

- Dependency – stakeholders who are dependent on an organisationʼs activities and operations in economic or financial terms

- Influence – stakeholders with influence or decision-making power (e.g. local authorities, shareholders, pressure groups).

- Representation – stakeholders who through regulation, custom, or culture can legitimately claim to represent a constituency

- Proximity – stakeholders that the organisation interacts with most, including internal stakeholders …etc

- Policy and strategic intent – stakeholders addressed through the policies and value statements

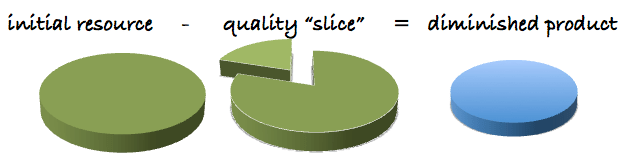

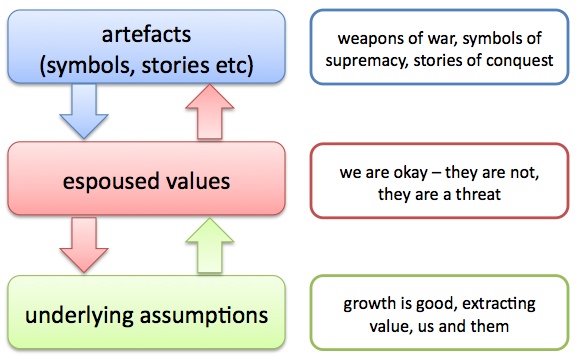

Threat bias

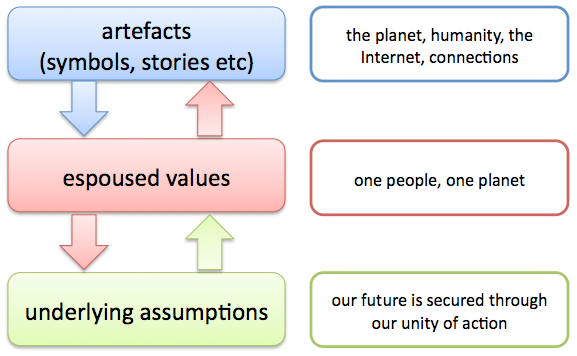

Notice how the bias in these factors is towards threat rather than opportunity? Sustainability initiatives, such as stakeholder engagement have developed in the context of threat. Corporates adopted social responsibility initiatives in response to criticism of their social and environmental performance. These were rearguard and defensive actions. Programmes such as the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) are an example. In this century, corporate are exploring sustainability initiatives as a source of innovation and competitive advantage. I described this shift in an earlier post – What is Sustainability 2.0?

If your organisation wants to express its sustainability initiatives as an opportunity, it would pay to change the factors used in stakeholder mapping to, at least, balance opportunity and threat.

This can be achieved in a number of ways:

- creating a higher weighting for opportunity factors

- reducing or combining threat factors

- adding opportunity factors.

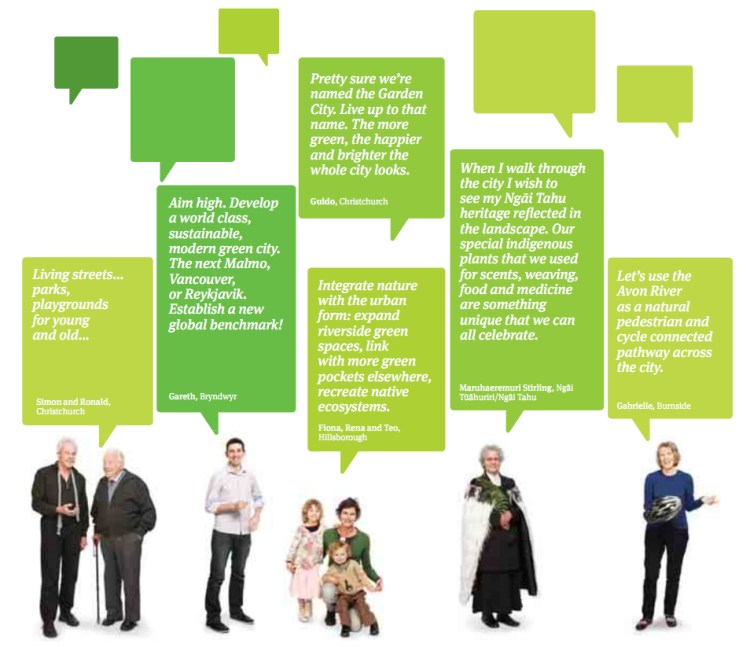

For example, you might combine threat factors such as responsibility and dependency, thus halving their influence in a final rating. Adding an opportunity factor, such as “potential for creating shared value” will further shift the balance. The “shared value” factor identifies those stakeholders the organisation can work with to create shared value. An example could be using a waste product from a stakeholder as a raw material, or supporting education initiatives to upskill the local population as a potential labour force.

Anthony Robbins identifies pleasure (opportunity) and pain (threat) as two motivating forces. Avoiding pain may be a stronger motivator than moving towards pleasure. Is this the case with sustainability and stakeholder engagement? If we are responding to perceived or potential threat we will probably develop a compliance mentality – and I don’t think compliance is that motivating. I would like to think that an aspirational approach based on pursuing engagement opportunities with stakeholders is more motivational. What do you think?